Last week I was knee deep in reading Peter C. Blum’s recent book “For a Church to Come: Experiments in Postmodern Theory and Anabaptist Thought.” Since I had also just finished an extended essay on the relevancy of the Brethren tradition for today, I was reading it with an eye toward understanding the intersection of Pietism and Anabaptism. In reading Blum’s excellent essay on feet washing, I was able to narrow the field of my question: How does the Pietist emphasis on the individual offer both a hurdle to overcome and a helpful corrective to Anabaptist collectivism?

I’ve written already on the intersection of the two traditions here. My question though, was primed by my good friend Scott Holland, a frequent reader and commenter of the NuDunker blogs. Scott, once a student with Yoder, offers a solid critique of Yoderian Anabaptism saying that “it offers an anthropology of the disciple but not of the person.” So I threw the question out to Scott and some fellow NuDunkers in order to explore just how Pietism might help us get to a better anthropology within the wider conversations of Neo-Anabaptism.

First, a bit of history. The 16th century Anabaptists and the 18th century Pietists, though connected in an impulse to recover a radical discipleship based in their reading of the New Testament, were separated by the grand shift toward the individual begun in the Enlightenment. That is to say that a kind of Cartesian turn toward the interiority of the human person was a significant difference between the Brethren and the Mennonites. Put another way, the Pietists worked within the framework of the Cogito- I think therefore I am. There are of course a ton of problems with this kind of Cartesian turn to the individual- most notably the separation of the interior and exterior self. Yet, for as much as academics have refuted Descartes’ system (especially through the work of Phenomenology), this sense of interior confidence is part and parcel to the Western sense of the self.

For the Pietists, a sense of religious certainty was to be found in the inner life. Though they might have balked at Descartes over emphasis on rationality, it was still the case that the individual was a clear source for religious understanding. Hence, many of the Pietists gathered in conventicles or study groups to explore the scriptures together. Hence, Luther’s emphasis on “scripture alone” found its logical conclusion among those small groups. They read together in order to better understand the scriptures and apply them to a life of holiness. Many of these groups were known for a rich spirituality, an affective reading of the scriptures that was deeply prayerful and mystical in tone. In a way, we might say that for the Pietists, Descartes maxim was better rendered “I pray, therefore I am.”

There were of course many Pietists who remained within their religious traditions. Some said that there were two churches- the visible church manifest in the institution and marked by both the lapsed and those in pursuit of holiness, and the invisible church comprised only of the holy. The Brethren, however, rejected that conception all together in the decision to baptize believers in water. In that decision they created a new, and only visible, community of discipleship. What is more, they followed the lead of the 16th century Anabaptists. Certainly, when we read the early writings of the Brethren, they would not have called themselves Anabaptists. As German historian and pastor Marcus Meier notes, the categories of Anabaptist and Pietist are modern labels applied to the past. Yet, there were streams of continuity between the 16th and 18th century reformers. What seems more operative, then, is a different sense of the person.

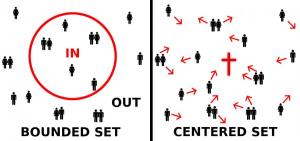

My emerging sense is that the Brethren- with a Pietist sense of heart and mind coupled with an Anabaptist desire for community and ethics- sought to temper the trajectory of radical individualism with a community of discernment and accountability. There are stories of persons whose mystical experiences were explored by the community and tested against the scriptures. One could not just say that “God told me so” without also asking fellow believers if this inner word coincided with the outer word of scripture. At the same time, the Pietist emphasis on conscience offered an equally critical tempering of an Anabaptist turn towards collectivism. In other words, the church was not an authoritarian herd but a community of persons seeking faithfulness and holiness together. There were certainly cases where such discernment resulted in a clear “No” on the part of the community, and yet as some stories show, the entertainment of the question was a two way street to test the community’s understanding as well.

This still leads me back to my original quest for a better anthropology. Though I assume that the early Pietists were the product of the Enlightenment turn towards the inner life of the individual, I am still wrestling with the anthropology that was at work in the Brethren synthesis of Anabaptism and Pietism. In many ways contemporary Brethren have camped out in either tradition, thus highlighting one as normative- either we are Anabaptists or we are Pietists, communitarians or individuals. My instinct is to say that both are true, but that still leaves open for debate how the heart felt mysticism of the Pietists finds grounding in the community of believers. That is to say that Pietism and Anabaptism practiced together avoids the pitfalls of collective authoritarianism on one hand and radical individualism on the other. Following Meier and others, the only difference I can discern in the historical narrative is the effect of the Enlightenment conception of the self. So the question haunts me- what is the better anthropology at work among the Brethren synthesis of Anabaptism and Pietism?