This post is part of a NuDunkers conversation on worship and authority. As is our pattern, a Google Hangout will take place Thursday, September 25 at 10 AM eastern. You can watch the conversation live here, or you can catch it on Youtube. You are all welcome to join the conversation in the comments, or write your own blog. Each of us will also follow up the Hangout with a post that will name what struck us in the conversation.

A healthy mistrust of authority runs through our modern DNA. With so many examples of those who have abused their role for personal gain, or at worst, those who have so exercised their authority to harm or even kill millions of people it is completely understandable. Even for us as Brethren, this mistrust of authority has theological roots. In the early days of the Dunker movement, authorities came in two general forms— the clergy and the princes. Those authorities were often the source of both political force and theologies that reinforced that same force. On the run from princes and bishops too closely aligned, the early Brethren often counted on a kind of radical democratic practice. Rather than count on the clergy and princes to define the terms, the community of believers functioned as the guide for the early Brethren.

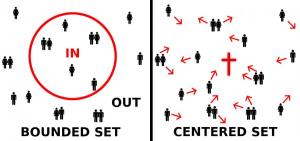

The problem with this brand of anti-authoritarian posture is that we all too often confuse (as a friend recently commented to me) being against authoritarianism with being against authorities— that is persons who, by training or office, have significant roles in our lives. In short, we basically rail against any person who speaks into our lives. “Who are you to tell me what to do or to believe.” While this is certainly understandable in some situations, we often rely on relationships with others before we trust them enough to grant them any authority.

The problem, of course, is that many people have significant power in our lives, whether we let them in or not. That is why worship can be such a contested space in our church lives. Those who write the songs, compose the litanies, and even shape the service have a significant role in giving shape to our theology, often without our explicit consent to their authority. When the words we use in worship both speak for us as a community and impact the ways we conceive of God, they have a unique role in our lives. Those persons who write and speak in worship have a kind of authority.

When those words conflict with our ideas, or even our way of life, the conflicts flare up. “Who are you to speak for me.” Sometimes, even the strongest of relationships are tested by this conflict of words and authorities.

The problem is, of course, that there simply are authorities. The question, then, is which authority do we allow to shape our actions and perceptions. Because we assume that the authority of the worship leader or preacher is contingent upon the role we overlook the skills and study that inform his or her functional authority. In fact, when the conflicts emerge it is precisely the skills and understanding that are dismissed out of hand. “You are just the preacher.”

James K.A. Smith helpfully shows in Desiring the Kingdom how there are many practices and stories that shape us. When we are confronted by the worship wars, we are inevitably choosing between two different sources of authority. Something, or someone, is informing our perceptions and understanding along the way, and we choose (possibly subconsciously) which authority has the most sway in our personal actions.

So a worship leaders have significant authority in the choosing of words and songs to guide the worship of a community. And I, for one, want someone who has also cultivated the theological authority to make those judgements outside of the worship gathering. However, I am well aware that our priesthood of all believers theology can undermine that skill based authority. In other settings it is the office or role that has the authority, with or without clear theological authority. We are, then, stuck in a bit of a conundrum. Our priesthood of all believers commitments balance out the times when role trumps skill, and yet that same commitment can equally undermine when skill and function are aligned.

Though I have no answers in naming this tension, I do find the words offered to new graduates of nearly every educational system offer us some way into the question. When a student “commences” their next stage of life and receive the degree for which they have toiled, he or she is told that in receiving the diploma that they also receive “the rights and the responsibilities pertaining thereto.” Those rights and responsibilities that strike me as the core question for us around authority in worship. Both the community and its leaders have significant rights and privileges. Yet, they are equally responsible to one another in the exercise of those rights.

What would it look like for us as people of faith to state clearly what we think those rights and responsibilities are? What would it look like for us to articulate the many other authorities that shape us, that we allow to define the terms and practices for us as individuals and communities? What if, instead of stating “Who are you to speak for me” we started with the questions of what rights are in conflict, or what authorities are competing in our midst?